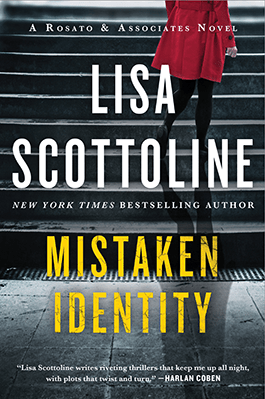

This is the first of Lisa’s books to become a New York Times bestseller, holding a spot on the paperback list for four weeks and going as high as number five! In Mistaken Identity, Bennie Rosato faces her greatest challenge by defending an accused cop-killer who claims to be Bennie’s twin sister. Readers and critics loved it, and Lisa received more reviews and emails about this book than any of her others. The novel received the coveted star awarded by Kirkus Reviews, which means the book is strongly recommended by this journal. Lisa’s response to the review was typically sophisticated: “Woweeee!” At fortysomething, Lisa should be above getting excited by such things as gold stars, but then she’d be way too cool to be any fun. Publishers Weekly also raved about the novel. You’ll find its review here as well.

“Continuing her run of coming up with the best hooks in the legal trade, Scottoline tosses Philadelphia lawyer Bennie Rosato her most challenging client — an accused cop-killer who claims she’s Bennie’s identical twin… Her biggest book yet.

– Kirkus Reviews (starred review)

“A multi-layered thriller that plunges Rosato & Associates into a maelstrom of legal, ethical and familial conundrums, culminating in an intricate, dramatic, and intense courtroom finale.”

– Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“A legal thriller that seamlessly combines courtroom strategies and family secrets. Scottoline raises the bar!”

– Robert K. Tanenbaum

“For ratcheting suspense, dynamic characters, and a master’s touch in the courtroom, it’s tough to beat Lisa Scottoline’s Mistaken Identity.“

– David Baldacci

Mistaken Identity

By Lisa Scottoline

CHAPTER 1

Bennie Rosato shuddered when she caught sight of the prison, as she pulled into its parking lot. The institution, exiled to a cement wasteland on the outskirts of Philadelphia, stretched three city blocks and stood five stories tall. Slits of bulletproof glass scored its black brick facade, the windows set lengthwise like razor cuts. The sign in front of the prison didn’t disclose that it was maximum security, but spiky guard towers, rows of cyclone fencing, and tangled spirals of barbed wire suggested strongly that murderers, sociopaths, and rapists were housed here. At least when they weren’t on parole.

Bennie pulled into a parking space, climbed out of her Ford Expedition, and walked down the sidewalk in June’s humidity, wrestling with her ambivalence. She’d stopped practicing criminal defense and figured she’d never see the prison again until the telephone call from a woman inmate, who was awaiting trial. The woman had been charged with the shooting murder of her boyfriend, a detective with the Philadelphia police, but claimed a group of uniforms had framed her. Bennie specialized in prosecuting police misconduct, so she threw a fresh legal pad into her briefcase and drove up to interview the inmate.

AN OPPORTUNITY TO CHANGE WITH DIGNITY, read the crooked metal plaque over the main door, and Bennie managed not to laugh. The prison was designed with the belief that vocational training would covert heroin dealers to keypunch operators, and since nobody had any better ideas, still operated on the assumption. She yanked open the heavy, gray door, an inexplicably large dent buckling its middle, and went inside. Stifling air assaulted her, thick with human sweat, generic disinfectant, and a cacophony of rapid-fire Spanish, street English, and languages Bennie didn’t recognize. Whenever she walked into prison she felt as if she were entering another world, until she remembered it wasn’t. And the sight evoked in her a familiar dismay.

The waiting room, packed with inmates’ families, looked more like day care than prison. Infants in arms rattled plastic keys in primary colors, babies crawled from lap to lap, and a toddler practiced his first steps in the aisle, grabbing a white sandal for support as he staggered past. Bennie knew the numbers; seventy-five percent of women inmates nationwide are mothers. The average prison term for a woman is a childhood. No matter how Bennie had judged her clients when she practiced criminal law, whether they had been brought to his place by circumstance or corruption, she could never forget that their children were the ultimate victims, ignored at our peril. Bennie couldn’t fix it no matter how hard she tried and she couldn’t stop trying. So she had finally turned away.

Bennie pressed the thought to the back of her mind and threaded her way to the front desk while the crowd chattered. Two older women, one white and one black, exchanged index-card recipes. Hispanic and white teenagers huddled together, a bouquet of backward baseball caps, laughing over photos of a trip to Hershey Park. Two Vietnamese boys shared the sports section with a white kid across the aisle. Unless prison procedures had changed, these families would be the Monday group, visiting inmates with last names A through F, and over time they’d become friends. Bennie used to think their good cheer a form of denial until she realized it was profoundly human, like the camaraderie she’d experienced in hospital waiting rooms, in the direst of circumstances.

The guards at front desk, a woman and a man, were both on the telephone. Female and male guards worked at the prison because both sexes were incarcerated here, in separate wings. Behind the desk was a panel of smoked glass that looked opaque but concealed the prison’s large, modern control center. A bank of security monitors glowed faintly through the glass, their chalky gray screens ever-changing. A profile moved in front of a lighted screen like a cloud in front of the moon.

Bennie waited quietly for a guard. It cut against her grain, since she questioned authority for a living, but she had learned not to challenge prison guards. They performed daily under conditions at least as threatening as those facing cops, but were acutely aware they made far less money and weren’t the subject of any cool TV shows. No kid grew up wanting to be a prison guard, after all.

Bennie waited, and in time, a toddler with covered bells on his shoelaces jingled over and stared up at her. She was used to the reaction even though she wasn’t conventionally pretty; she stood a six feet tall, strong and sturdy. Her broad shoulders were emphasized by the padding of a yellow linen suit, and wavy hair the color of pale honey spilled loose to her back. Big blondes generally caught the eye, approving or no, and Bennie smiled at the little boy to show she wasn’t a banana.

“You an attorney?” asked the guard, hanging up the phone. She was a light-skinned black woman in a jet-black uniform and pinned to her heavy breast was a badge of gold electroplate. The guard’s hair was been combed back into a tiny bun from which stiff hairs sprung like a pinwheel. Her short sleeves were rolled up, macho-style.

“Yeah, I’m a lawyer,” Bennie answered. “I used to have an ID card, but I’ll be damned if I can find it.”

“I’ll look it up. Gimme your driver’s license. Fill out the request slip. Sign the OV book, for official visitors,” the guard said, on auto-pilot, and pushed a yellow clip ID across the counter.

Bennie produced her license, scribbled a request slip, and signed the book for official visitors. “I’m here to see Alice Connolly. Unit D, Cell 53.”

“What’s in the briefcase?”

“Legal papers.”

“Put your purse in the lockers. No cell phones, cameras, or recording devices. Take a seat. We’ll call you when they bring her down to the interview room.”

“Thanks.” Bennie hunted for a chair and spotted one in front of the closed window for the cashier and clothing exchange. The families had left the seat vacant because it was the equivalent of a table by the front door in a busy restaurant. When it opened, the exchange would be mobbed with families dropping off personal items, like the plastic rosaries the inmates liked to wear and the do-rags needed for gang identification. And they always welcomed extra cash; for what, Bennie didn’t want to speculate. She wedged into the seat, next to a stocky grandmother who smiled at her when she spotted her briefcase. A prison waiting room is the only place where a lawyer is a welcome sight.

“You’re up, Rosato,” called the guard.

Bennie rose and went through the Friskem metal detector to the other side of the front desk. She set her briefcase down on the gritty tile floor and raised her arms while the female guard ran a professionally intrusive hand down her arms and sides. “Tell me I’m the only one,” Bennie said, and the guard half-smiled.

“Go on up, girl.”

“Fine, but next time I expect dinner.” Bennie picked up her briefcase as a male guard unlocked a gray metal door, double-thick. Attorneys signed a no-hostage waiver to get an initial ID, and once she passed through the door, she’d be locked in with a general population of violent inmates packing homemade knives, straight-edge razors, garrotes, shanks, forks twisted into spikes, spikes twisted into spears, and even a blowtorch or two. Bennie’s only weapons were a canvas briefcase and a Bic ballpoint. Anybody who believes the pen is mightier than the sword hasn’t been inside a maximum security prison.

She crossed the threshold with a nonchalance that fooled no one and walked down a narrow gray corridor, as stifling as the waiting room, but mercifully quiet. The only sounds were echoes of faraway shouting and the clatter of her pumps down the hall. She hit a battered button and rode the empty cab to the third floor. On the landing was a smoked glass window that obscured the guard sitting behind. Bennie passed her request slip under the dark window and it was grabbed by a large hand. “Room 34,” said the guard’s muffled voice, and the door to Bennie’s right unlocked with a mechanical ca-thunk and opened a crack.

She walked through the door to another gray corridor, this one with a set of doors on the left, each leading to a gray cubicle. Inmates entered the cubicles from doors off a secured hallway on the other side, and all the doors locked when they closed. Each cubicle, about four-feet- by-six, contained two chairs facing each other and a tan wall phone for calling the guard. Only a Formica counter divided felon from lawyer. Though it had never bothered Bennie before, for some reason it felt inadequate today. She walked to the end of the corridor, opened the door to Room 34, and did a double-take on the spot. “Are you Alice Connolly?” she asked.

“Yes,” the inmate answered, with a cocky smile. “Surprised?”

Bennie eyed the prisoner up and down, her gaze ending its bewildered journey at the inmate’s face. Alice Connolly looked like a prettier, albeit streetwise, version of Bennie herself. Her hair was a brassy, fraudulent red and had been scissored into crude layers. She had Bennie’s broad cheekbones and full lips, but wore enough makeup to enhance those features. She looked as tall as Bennie but was model-thin, so her orange jumpsuit seemed almost fashionably baggy. But it was her eyes – round, blue and wide-set – that matched Bennie’s exactly, rendering the lawyer momentarily speechless.

Connolly extended a hand over the Formica counter. “Pleased to meet you. I’m your twin. Your identical twin.”

Bennie stared at the inmate, stunned. It wasn’t possible. She didn’t have a twin. She didn’t even have a sister. Her briefcase slipped from her fingers and fell to the floor with a heavy thwap.

©1998 by Lisa Scottoline. All rights reserved.

Mistaken Identity

Questions for Book Clubs

- Read the Acknowledgements. How weird is it that Lisa didn’t know she had a half-sister? How often does this happen and not make it to Montel? Did it happen to anyone you know? And if something like that happened to you, would you put it in a book for the whole entire world to read about? Where do authors get their ideas and why don’t they come up with better ones?

- When is a good story an invasion of privacy?

- Would you defend your twin on a murder charge? Should Bennie? Do you understand why she does?

- Is Grady hot enough for you? Is it weird that he’s younger than Bennie?

- What is justice? Is it justice if Alice goes free, or not?

- This book is told in the third person, unlike Legal Tender which has a single point of view. Like it better or worse? Why did Lisa make this decision? Anything about the story, or was she just in the mood? You know how silly she can be.

- This boxing thing is a big part of the book. Do we like it? Why is it here? Does it inform character? How did Lisa do with her boxing lessons? Is it okay to say “sucks at boxing” in a book club?

- Do we like Lou?

- Why does Lisa put us through a parent’s death? Is she just a big meanie?

- What did we think of the courtroom scenes? Agree with the verdict?

- Where did Alice go? Is she dead or will she come back? Hint: Heh heh.